Experiences of discrimination and being out are two main factors driving and influencing experiences of poor mental health and burnout are among those LGBT+ staff in HE institutions.

Written by: Rei Hirayama

In our last blogpost, we discussed the high rates of mental health issues and burnout among LGBT+ staff in Higher Education (HE) in the UK. Today we take a further look at the role of gender- and sexuality-related phobic languages and humiliation[1]and show how experiences of micro aggression significantly affect LGBT+ staff’s feeling of competency at work.

“Increasingly exploitative of workers, dismissive of foundational change and academic freedom dehumanize far too LGBT+ people, making us miserable and sick”

This detrimental effect also leads to stronger feelings of being isolated and higher incidences of burnout and mental health issues among LGBT+ staff, and may also affect career progression and general wellbeing among these staff groups.

This is important because it shows us not only ‘who’ experiences burnout and mental health issues but also ‘how’ these stress reactions are structurally caused among LGBT+ staffs in HE (see the previous post).

In our analysis, we have sought to identify what causes mental health and burnout among LGBT+ staff in HE. We did so by exploring the causal pathways by which specific ‘gender-related stressful experiences’ trigger deterioration of stress reactions (burnout and mental health) among LGBT+ staffs in the HE, UK.

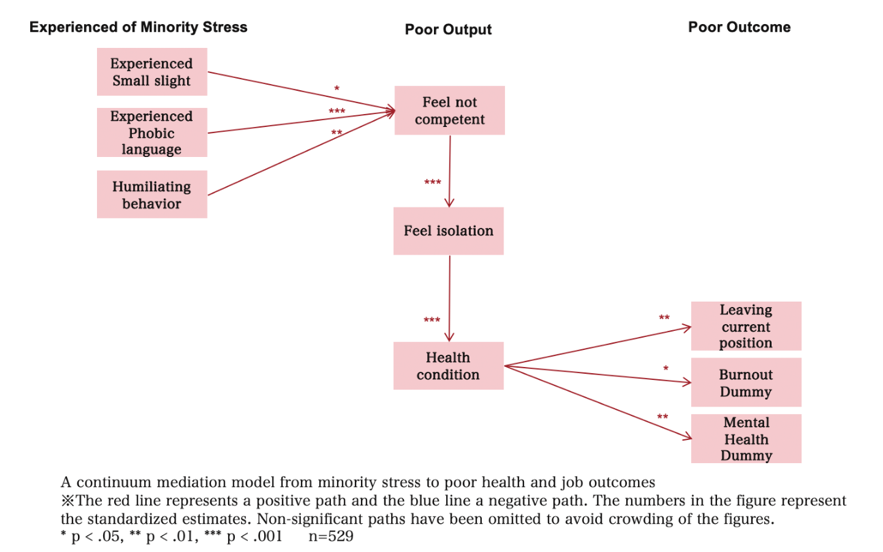

Figure 1: Path to Stress reactions

Referring to Kubo, M. (2007). Burnout. Japanese Journal of Labour Research. 558, pp. 54-64

The model was set out using the Minority Stress Theory. This builds on work by King and Stoneman (2017) that shows how the experience of discrimination and expressions of internalised homophobia directly impacts the interpersonal network that LGBT+ staff have in their workplace (differently to different types of LGBT people). This consequently raises the probability of experiencing mental health problems (Kneale et al., 2021), lack of well-being (Lloren & Parini, 2017), lower pay, fewer employment opportunities and worse career progression than non-LGBT employees have (Sears and Mallory, 2014).

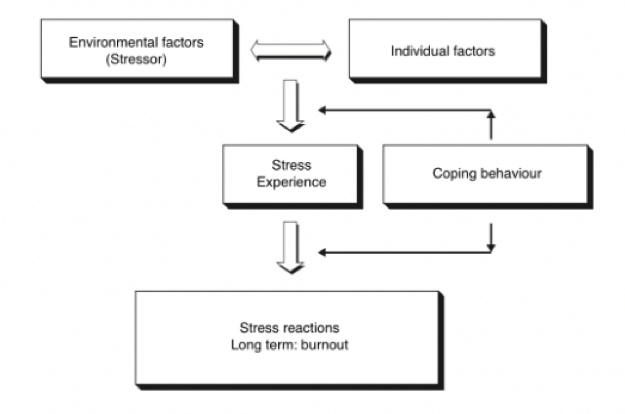

Using the above model, ‘minority stress → poor output → poor outcome’ Figure 2 outlines our findings. This pathway shows that experiences of micro-aggressions and phobic language in the HE working environment cause short to medium psychological and physical symptoms, followed by severe long-term stress reactions among our respondents. I analysed whether the theory of this pathway (causality) also applies to the general HE working environment in the UK context.

Figure 2: Result of Minority Stress Theory

Our analysis shows that the experience of gender and sexual-related phobic language and micro-aggressions strongly lower LGBT+ staff’s ‘feeling not competent’ and ‘feeling isolated’ and leads to burnout and mental health issues. This is supported by findings in our qualitative work where participants describe common experiences of bullying or discrimination, which can cause depression and anxiety leading to an increase in the burnout. In addition to this, open box answers also show the other path that ‘online job’, ‘lack of sympathy from supervisors’ and ‘unclear communication from the university’ lead to psychological loneliness.

“The transition to online was very stressful at times due to inadequate support for online teaching and I had to put a lot of effort into looking after my own mental wellbeing.”

“A talented academic postdoc on my team, gay woman, with a disabled child, who recently returned from breast cancer surgery was made redundant with the minimum of communication with her and me from HR at departmental and central level. The leadership team are mostly escaping the sinking ship, and the remaining leaders pretend it is service as normal. No policies were carried out in practice.”

Despite the advancements made by the Civil Partnership Act (2004) and the Equality Act (2010) in the UK, our research found evidence that LGBT+ staff in HE still face many difficulties. We have begun to unravel the structures that cause burnout and mental health problems from the perspective of gender and sexual orientation in our project showing an urgent need to improve working conditions for LGBT+ staff in HE.

As our analysis has shown in the previous and this blog, people from gender and sexual minorities are significantly more likely to have mental health and burnout issues compared to hetero-cisgender people. Indeed, the survey indicates that harm from gender-related small slight, phobic language and humiliation, causes low self-competency, mental health and burnout issues, and is two to three times more common among non-heterosexuals and non-cisgender people than hetero-cisgender people.

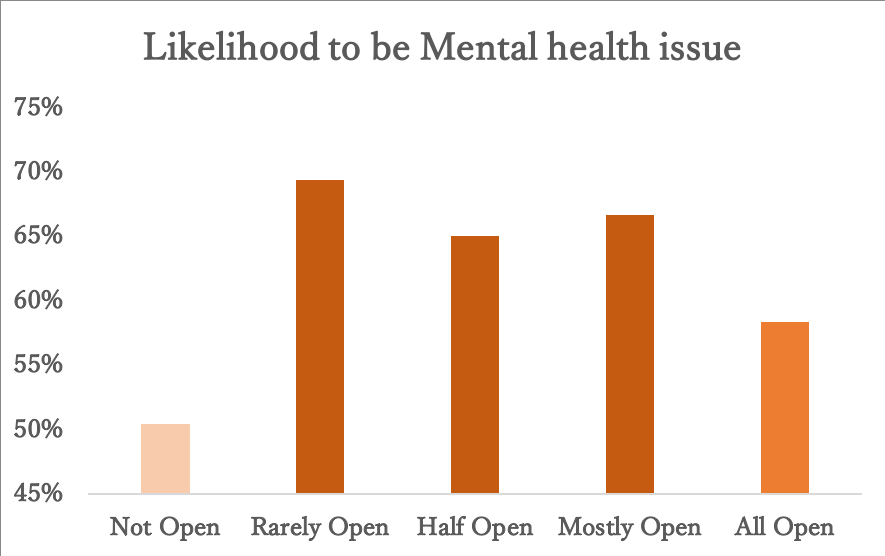

A final thing to note is the environment where the stress associated with the coming-out process and the different degrees of outness all lead to a higher likelihood to have mental health. The previous blog showed that not being open about gender identity and sexual orientation at work can significantly prevent stigma, discrimination, and long-term stress reactions (minority stresses). It means outness is not only about individual factors but more environmental factors as a stressor.

Due to the fearing identity rejection, discrimination and backlash from work colleagues, many individuals described coming out as one of the most stressful experiences in their life (Bialer and McIntosh, 2016). Since being out at work often turns out to be psychological health problem (Chamberland et al., 2009), LGBT+ employees tend to hide their identities (Sears and Mallory, 2014). This was especially the case for the staff who works on the non-gender disciplines (Mathematics, Business, Physics, etc.) in our data as being open is not necessarily required although there is a burden of suppressing own identity.

Many respondents commented that “if we did not hide it, we would be treated unequally and opportunities for promotion would never come”.

Some studies claim a positive relationship, with employees who disclose their sexual orientation in the workplace being able to distinguish between their public and private lives and, as a result, experience less stress and anxiety about being exposed. In fact, some commented that being out makes us safer, and as Figure 3 shows, it is less likely to be a mental health issue than being half out and half in. The advantage of not disclosing gender identity and sexual orientation still outweighs being all out. According to Lloren and Parini (2017), the condition for being all out with no stressor is that LGBT-Supportive Workplace Policies are working throughout the work environment, and this seems not yet to have been applied to the working environment in UK HE institutions.

Figure 3: Likelihood of mental health due to outness

We are now required to deepen our analysis based on more different aspects to address more potential needs and unidentified problem structures associated with LGBT+ people. For more information about the project, the in-depth findings and next steps see LGBT-HE and UCU, and stay tuned for the next blog.

References:

Bialer, P. A., and McIntosh, C. A. (2016). Discrimination, stigma, and hate: The impact on the mental health and well-being of LGBT people. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(4), pp. 297-298.

Chamberland, L., Bernier, M., & Lebreton, C. (2009). Discrimination et stratégies identitaires en milieu de travail. Une comparaison entre travailleurs gais et travailleuses lesbiennes. In L. Chamberland (Ed.), Diversité sexuelle et construction de genre pp. 221-262.

King, A., and Stoneman, P. (2017). Understanding SAFE housing – putting older LGBT people’s concerns, preferences and experiences of housing in England in a sociological context. Housing, Care and Support, 20(3), pp. 89-99.

Kneale, D. et al., (2021). Inequalities in older LGBT people’s health and care needs in the United Kingdom: a systematic scoping review. Ageing & Society, 41(3), pp. 493-515.

Kubo, M. (2007). Burnout -stress in human service jobs-. Japanese Journal of Labour Research. 558, pp. 54-64

Lloren, A., and Parini, L. (2017). How LGBT-supportive workplace policies shape the experience of lesbian, gay men, and bisexual employees. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(3), pp. 289-299.

Sears, B., and Mallory, C. (2014). Employment discrimination against LGBT people: Existence and impact.

[1] Humiliation indicates language that reduces LGBT+ people to a lower position in one’s own eyes or other’s eyes. This often leads to the feeling of being ashamed or losing respect for yourself by force or voluntarily.